Was Dikembe Mutombo on the flight?

Mike Riley wondered as he stood in the waiting area at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, D.C. It was the late 1980s, when you could walk right up to the gate and meet your party.

Riley was there with Craig Esherick, a fellow assistant men’s basketball coach at Georgetown. They brought along NBA player Michael Jackson, who had played guard for the Hoyas before the Sacramento Kings, and a friend of his who spoke French.

“With all the languages that Dikembe could speak, he could not speak English,” Riley recalls.

The coaches were skeptical. They had learned about Mutombo, as Riley recalls, through a family connection. But they had gotten tips on African players before. The players weren’t as tall as advertised, and one of them simply couldn’t jump.

“We got the idea that people were just calling, trying to sell the kid, to get the kid to come to the United States,” Riley says.

This time, they weren’t even sure the player, from Congo, was on the plane.

As the stream of people deboarding dwindled to the crew, the coaches asked a flight attendant if anyone was left. She said there were a couple of stragglers.

“Is there a tall guy?” they asked.

“Oh God, he is really tall,” she replied.

When Mutombo finally appeared in the doorway, he had to bend his head down to walk through it.

“Uh oh, we may have something here,” Riley thought.

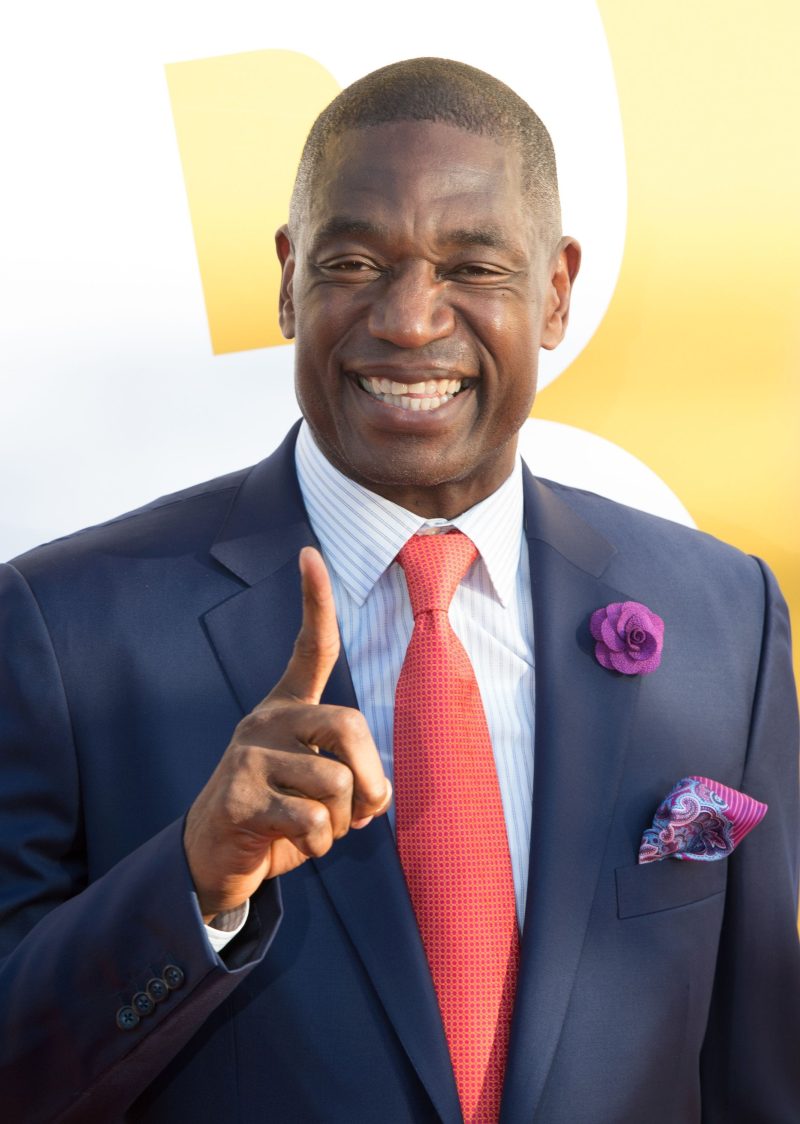

Every meeting with Mutombo, who died late last month at 58, just seemed unforgettable. The gentle giant of a man would go on to reach the Basketball Hall of Fame for his collegiate and professional success, but his large footprint leaves a legacy far beyond the court.

He was a global ambassador for the NBA and a leader in humanitarian efforts for his home continent. He was a loving father, a model teammate and an advocate for making kids’ lives better.

And as the NBA season dawns next week, he is someone who will be sorely missed across the basketball community.

“He always brought a smile,” says Jerome Williams, a Hoyas power forward from 1994 to 1996 who was mentored by Mutombo and later traveled with him on goodwill trips back to Africa when the both were pros.

USA TODAY Sports spoke with Williams ad Riley, who coached Mutombo for four years at Georgetown, to relive his memory. And there are lessons all of us – parents, coaches and athletes – can learn from the big guy with the husky voice and perpetually wide grin that seemed to warm everyone he met.

“His laugh sounded like the Cookie Monster,” Williams says. “He could speak several different languages, and sometimes you thought he was speaking a foreign language when he was speaking English, which would make you laugh.

“He always brought joy to any situation.”

Be eager to learn, to try new things and to better yourself

When Riley and the others got in the car at Dulles airport to drive to Georgetown’s campus, they learned Mutombo did speak English. Well, at least two names could be distinguished through his heavily accented words: Patrick Ewing and Alonzo Mourning.

At that moment, there were no thoughts of Mutombo joining the two famous centers on the school’s Mt. Rushmore of big men. No one was even sure if he would play a game for the Hoyas.

In the grainy footage the coaches had seen of Mutombo, he had been playing on what looked like grass or dirt, and the baskets appeared about 8 feet high.

“Can you jump and touch the rim?” Georgetown coach John Thompson asked him when he got to the gym on campus.

Mutombo walked over to the regulation-sized 10-foot hoop, got on his tiptoes and hit the bottom of it with his finger.

“Come on, son,” Riley recalls Thompson saying. “Come on upstairs. We gotta talk.”

During the long conversation, the coaches saw a guy who “doesn’t come with any real baggage,” Riley said. He simply wanted to go to school and to learn.

“You root for people that are good people,” Riley says. “He used every bit of 7-2. Now there are people that are tall that don’t use their height, but he used every bit of the 7-2, because he wasn’t well-versed in basketball.”

Mutombo’s height was about all he had going for him. He couldn’t pass very well and didn’t understand where to stand on the court.

We can look at life’s challenges as either struggles or opportunities. It was apparent Mutombo viewed most everything he encountered as an opportunity.

“Dikembe took five regular courses at Georgetown, while also taking a course to learn English,” Riley says. “I think that’s just amazing to me, how well he did and how well he made the adjustment to being able to speak English.

“I guess where he comes from, this is it, I’m here. You can walk up to the cafeteria and have free meals. There’s probably a commitment to making sure that you stay here and you do well here.”

Mutombo was half a world away from his native Zaire, but that distance was a matter of perspective. He was now at a prestigious university playing for one of basketball’s foremost coaches.

As it turns out, the coach was feeding off him, too.

Don’t rely on one skill. Instead, be a ‘filling station’

A new language was one hurdle. Mutombo also had to learn how to speak basketball: being at the elbow, sliding down to the wing, going to the weak side or even simply to “drive!” None of the slang meant anything to him.

Thompson had to physically move Mutombo to spots on the floor and then explain the terminology. Mutombo soaked up everything.

‘Dikembe is a refreshing person to work with,’ Thompson said in 1990, according to USA TODAY’s Steve Berkowitz, who then was at The Washington Post. ‘He’s like a filling station for a coach. I can go in and get new energy from him. I enjoy him.

“I think that’s a part kids don’t understand. They come to receive, but they don’t realize that they also give. Dikembe is that way. You can get angry at him and he understands that you’re not trying to personally attack him. He says a lot of things when I’m angry that will make me break into a smile. And at this age, you need that filling station.’

While Mutombo’s height brought him to the USA, his willingness to figure out the intricacies of basketball kept him here.

“He wasn’t ultra-talented but he took what he learned and he used that,” Riley says. “You don’t really develop because of the coach. I shouldn’t say you don’t, you do, but you really develop because you want to develop.”

Mutombo played intramural basketball and in the school’s summer Kenner League. Through repetition, he learned how you need timing to block shots.

During his first season playing at Georgetown (1988-1989), he set a Big East record with 12 blocks during a game against St. John’s.

“His teammates respected him an awful lot because they knew that if they weren’t playing great defense, that he was going to be the emergency at the glass,” Riley says. “They loved him, and they loved to talk about where he was from. They would tease him about being in America. And he would say, ‘You Americans, got it too soft.’

“There was no animosity. He was just as happy about somebody else doing something as he would have been for himself. And he had that big, deep voice that just boomed out.”

Ohhh, ohhhh, ohhh, Coach Riley!

Riley’s wife couldn’t stop laughing when they opened a restaurant door in Georgetown and Mutombo greeted them that way.

“That was the first time she had ever met him,” Riley says. “So he shook her hand and he starts telling a story. I said, ‘Come on, let’s go. (No) time to listen to Dikembe’s stories.’ ”

You can always find ways to make your team better

Mourning, who tutored Mutombo at hoops, once said it was impossible not to like Mutombo. That first season together, they reached the Elite Eight and the pair formed a formidable front line on two more NCAA tournament teams.

For the rest of his life, Mutombo returned the favor many times over.

“He was always helpful in a big brother way, just letting us know we could do it,” Williams says.

Williams arrived at Georgetown in 1994 as a transfer from a junior college in Maryland, He found himself matched up against a guy who would be crowned the NBA’s defensive player of the year the following season.

“Dikembe was like the ultimate role model,” says Williams, who went on to reach a Sweet 16 and Elite Eight with the Hoyas and play nine seasons in the NBA. Mutombo played 18.

“He wasn’t the scorer on the team,” Williams says. “He wasn’t the main guy. He was rebounding. He’d set screens. He’d block shots. He taught me that if I was a good rebounder, I could be a good role player as well.”

Develop a number a skills. Play a number of roles or positions. It’s a good lesson for any kid trying to make a team.

Mutombo had another.

“He was gonna make sure he blocked as many of our shots as possible to let us know it wasn’t gonna be easy, and that pushed all of us,” Williams said.

As he became an established star, Mutombo punctuated those blocks by waving his finger to the crowd.

“The ‘no, no, no,’ finger wag became infamous, and that’s what he was known for and he branded it,” Williams says. “And that was like the best thing because where he said, ‘No, no, no,’ on the court, he always said, ‘Yes, yes, yes’ to people in the community.”

Coach Steve: Jerome Williams coaches kid athletes to market themselves at an early age

Don’t forget where you come from, and send the elevator back there

Williams says their friendship began when Mutombo invited him to his house for a barbecue during those collegiate summers. The relationship continued from there.

“I saw at a very young age his interactions with his kids,” Williams says. “Good fun-loving father, being there for his kids, jerking around with his kids, teaching his kids the proper way in life. Just like he would do for everybody else.”

It was the start – and a foreshadowing – of the work they would do in Africa for the NBA. Mutombo invited him to South Africa and Botswana to aid in building facilities for kids and, of course, play basketball with them.

“We would just encourage them never to give up, believe in themselves, and to always try to be the best. No excuses. That was his message,” Williams says. “A lot of NBA players come from Africa, and he was one of the trailblazers that really spearheaded Basketball Without Borders and gave it a lot of fuel.

“And from Africa, they were able to move into places like China and India and South America, and I went on a lot of those trips. The NBA now is such as global game, and basketball is such a global game, but it started with a lot of the outreach that he was doing.”

Mutombo used his financial resources and returned to provide aid to his native country, which has been known as the Democratic Republic of Congo since 1997.

He was instrumental in building the Biamba Mari Mutombo Hospital there, named in honor of his mother.

In recent years, Mutombo was a fixture at Hoyas games, watching his son Ryan play for his alma mater. (Mutombo and his wife, Rose, had seven children, including four nieces and nephews they adopted.)

Sometimes Williams, whose daughter Gabby was in the same graduating class as Ryan, would join him courtside.

“His famous quote ― I still use it to this day when I meet with kids and I tell ‘em that whenever you take the elevator up, meaning you make it to your dreams and get to see the top, make sure you go back down to bring somebody else up.”

Mutombo credited his grandmother with the quote. It also seems appropriate applied to him, a man who always found his way home.

“I always say that I’m glad that I had opportunity to cross paths with certain people, and Dikembe is definitely one of them,” Riley says. “He showed me something that I hadn’t seen before. He always made me feel happy when I was around him. And he always was happy to see me whenever we ran across paths to each other.

“So I just think that his passing is tough for a lot of people.”

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.