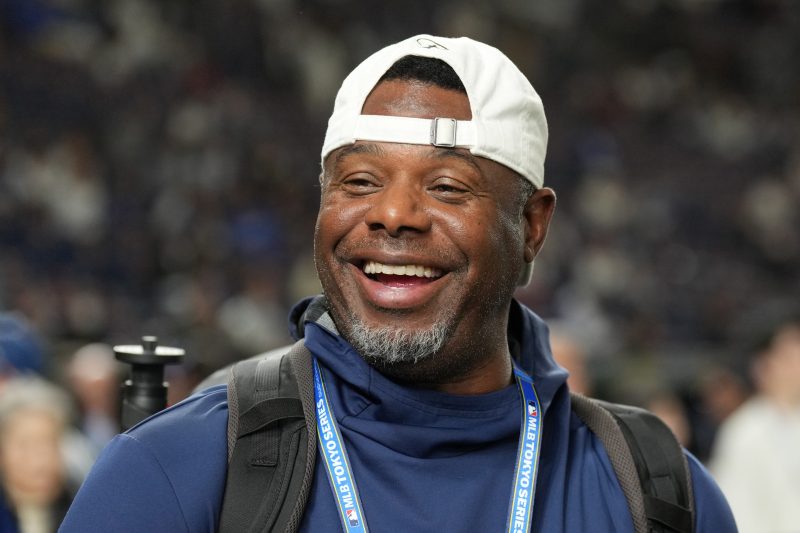

To Ken Griffey Jr., the picture – and the goal – is simple.

“If you look at what’s going on in baseball, (there are) a lot of kids of color who are not playing baseball even though they may love the game of baseball,” Griffey told USA TODAY Sports by phone. “They’re not getting the recognition that they would like to advance to the next level.”

That was the initial motivation to start the HBCU Swingman Classic, which brings together 50 Division I baseball players from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Now in its third year, the “Swingman” – named after Griffey – is a chance for the athletes to perform on a bigger stage as Major League Baseball begins its All-Star Week celebrations at Truist Park, home of the Atlanta Braves, on Friday, July 11 (7 p.m. ET, MLB Network).

“For me, it’s just an opportunity to give some of these kids an opportunity to be seen,” said Griffey, who hit 630 career home runs and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2016.

Sixteen HBCUs will be represented in the game. There will be a flavor of Black baseball and Atlanta throughout the festivities. Brian Jordan will manage the “National League” squad, while fellow David Justice will lead the “American League” team. Martin Luther King III was scheduled to throw out the first pitch but can no longer attend, while Emily Haydel, the granddaughter of Hank Aaron, will be a sideline reporter on the broadcast.

But the Swingman goes beyond racial lines. Any player who attends a HBCU is eligible to play in the game.

“Because there are plenty of kids who are White and don’t have money and they go to HBCUs and they want to continue to play,” Griffey said. “Yes, you’re going to see a few more Black people playing, but it’s not about the color of your skin. It’s the school that you go to.”

With a more streamlined and tapped-in selection process thanks to expanding relationships with HBCU coaches, the talent pool at Swingman has only improved since its inception. Both MLB employees and MLB Players’ Association officials are part of the selection panel for players who “may have been overlooked.”

Three players from the event were selected in the draft after the inaugural 2023 edition and two players were taken last year.

Griffey thinks baseball has to take a page out of the pre-NIL college football recruiting manual that set up the championship programs such Nick Saban’s Alabama Crimson Tide or Dabo Swinney’s Clemson Tigers.

“I think the sad part is that the scouting department has gone away from trying to find these diamonds in the rough,” Griffey said.

Instead, scouts rely too much on data and other advanced metrics, in Griffey’s opinion. It comes down to manpower and placing the scouts with the proper mindset in the applicable areas. As a senior adviser to commissioner Rob Manfred, it’s a conversation Griffey is having in baseball’s most powerful rooms.

“It has been discussed and it’s getting to a point where it’s coming around,” he said. “It’s just going to take some time. Back when my dad played, people went everywhere. Now, if it’s not on a computer … they can’t understand talent unless they see it. I sat there and watched. That eye test. That hearing test. ‘What does it look like when it comes off the bat? What does it look like when he throws the ball?’”

But the Swingman isn’t about the eye test or advanced analytics. It’s about opportunity, and it’s why the game should be a staple as long as he has a voice in the league office.

“Our kids need to be seen,” Griffey said. “Because they don’t have the facilities where they can go in there and measure exit velo, spin rate. All these things cost money and they just don’t have that type of money.

“You give a kid an opportunity to be successful, and that’s all you ask for.”